Title: Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity

Author: David Allen

Year: 2015

Pages: 352

In this crazy busy world, staying organized, and managing tasks efficiently can feel like an uphill battle, right?

Enter David Allen’s “Getting Things Done” world, a timeless classic book that offers practical solutions for tackling the chaos of modern life.

Reflect for a moment on what it actually might be like if your personal management situation were totally under control, at all levels and at all times. What if you could dedicate fully 100 percent of your attention to whatever was at hand, at your own choosing, with no distraction?

It is possible. There is a way to get a grip on it all, stay relaxed, and get meaningful things done with minimal effort, across the whole spectrum of your life and work.

You can experience what the martial artists call a “mind like water” and top athletes refer to as the “zone,” within the complex world in which you’re engaged. In fact, you have probably already been in this state from time to time.

Allen’s approach in Getting Things Done is practical, actionable, and adaptable, making it applicable to a wide range of individuals from different backgrounds and professions.

As a result, I gave this book a rating of 8.5/10.

For me, a book with a note 10 is one I consider reading again. Among the books I rank with 10, for example, is Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People.

3 Reasons to Read Getting Things Done

Achieve Clarity

Allen’s method emphasizes capturing all tasks and ideas into a trusted system, providing clarity and peace of mind by clearing mental clutter.

Boost Productivity

By breaking down tasks into actionable steps and establishing clear priorities, readers can enhance their productivity and accomplish more in less time.

Reduce Stress

Implementing Allen’s strategies can help individuals feel more in control of their workload, leading to reduced stress levels and improved overall well-being.

Book Overview

Think about the last time you felt highly productive. You probably had a sense of being in control; you were not stressed out.

You were highly focused on what you were doing, time tended to disappear (lunchtime already?), and you felt you were making noticeable progress toward a meaningful outcome.

Would you like to have more such experiences?

Getting Things Done by David Allen is a practical guide to managing tasks and reducing stress. With a focus on simplicity and clarity, Allen’s method provides a roadmap for achieving productivity and peace of mind.

Getting Things Done offers valuable insights and actionable strategies for anyone seeking to enhance their productivity and effectiveness.

In order to deal effectively with all of that, you must first identify and collect all those things that are “ringing your bell” in some way, and then plan how to handle them. That may seem like a simple thing to do, but in practice most people don’t know how to do it in a consistent way.

Allen’s method focuses on capturing all tasks, ideas, and commitments into a trusted system. This clears mental clutter and provides clarity on what needs to be done.

One key idea in the book is the importance of clarifying next actions. Allen suggests breaking down tasks into actionable steps to prevent overwhelm and procrastination.

Many people find it hard to put in the effort needed to figure out what something really means to them and what they should do about it. We’re not taught to think about our tasks before doing them. Often, our day is already planned out by the tasks waiting for us at work or the chores and responsibilities we have at home.

By identifying the specific next actions required, we can move tasks forward more effectively.

Another important lesson is the need for regular reviews. Allen advocates for reviewing our task lists and commitments regularly to ensure nothing falls through the cracks. This helps us stay organized and on track with our goals.

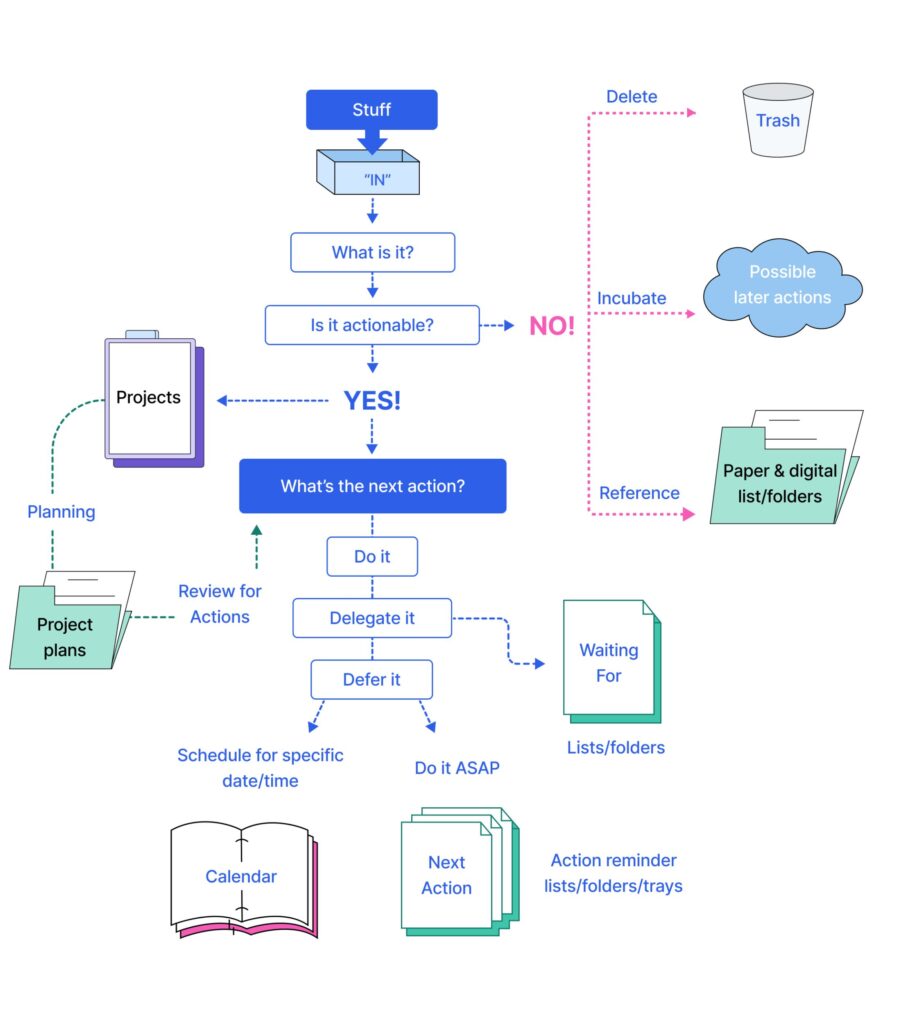

At its core, GTD is about capturing, clarifying, organizing, reflecting, and engaging with tasks in a structured manner.

These are the five steps of GTD:

- Capture everything that has your attention

- Clarify what needs to be done

- Organize information so that you can find it later

- Reflect and prioritize your work

- Engage in the right activities

The first step is to capture all tasks, ideas, and commitments into a trusted system, whether it’s a physical notebook, a digital app, or a combination of both. This ensures that nothing slips through the cracks and helps clear mental clutter.

Once tasks are captured, the next step is to clarify what needs to be done. This involves breaking down tasks into actionable steps and identifying the specific next actions required to move each item forward.

By achieving clarity on what needs to be done, individuals can avoid feeling overwhelmed and procrastinating on important tasks.

After clarifying tasks, the GTD method emphasizes organizing them systematically. Tasks are categorized based on context, priority, energy levels, and deadlines.

Context-based lists such as @Home, @Work, or @Computer help individuals focus on tasks that are relevant to their current location or resources.

Prioritizing tasks ensures that the most significant and time-sensitive items are addressed first, leading to increased efficiency and productivity.

Finally, regular reviews are essential to maintaining the GTD system. By periodically reviewing task lists, commitments, and priorities, individuals can ensure that everything remains up-to-date and aligned with their goals.

This reflection process allows for adjustments and refinements to be made as needed, keeping the system dynamic and adaptable to changing circumstances.

Overall, the GTD method provides a clear and actionable framework for managing tasks, reducing stress, and achieving greater productivity in both professional and personal life.

Getting Things Done book also emphasizes the value of organizing tasks systematically. By categorizing tasks based on context, priority, and energy levels, we can focus on what matters most at any given moment.

This prevents us from feeling overwhelmed and helps us make better use of our time.

Overall, Getting Things Done offers practical strategies for improving productivity and reducing stress. By implementing Allen’s methods, readers can reclaim their time, achieve greater clarity, and accomplish their goals with ease and confidence.

What are the Key Ideas

Capture Everything

Allen advocates for capturing all tasks, ideas, and commitments into a single, trusted system. This could be a physical inbox, a digital app, or a combination of both.

Clarify Next Actions

Once tasks are captured, it’s essential to clarify the specific next actions required to move each item forward. This clarity eliminates ambiguity and prevents procrastination.

Organize Systematically

Allen introduces a systematic approach to organizing tasks based on context, time, energy, and priority levels. This helps individuals focus on what matters most in any given moment.

Review Regularly

Regular reviews of the entire system ensure that tasks are up-to-date, priorities are aligned, and nothing falls through the cracks.

What are the Main Lessons

Embrace Mind Sweep

Conduct a thorough “mind sweep” to capture all open loops, commitments, and ideas from your mind and external sources.

Use the Two-Minute Rule

If a task can be completed in two minutes or less, do it immediately. This prevents small tasks from piling up and becoming overwhelming.

Employ the 4 D’s

Do it, Delegate it, Defer it, or Delete it. This decision-making framework streamlines task management and prevents indecision.

Establish Context-Based Lists

Organize tasks into context-based lists such as @Home, @Work, or @Computer to ensure you tackle tasks efficiently based on your current location and resources.

Prioritize a Weekly Review

Conduct a weekly review to reflect on accomplishments, reassess priorities, and set intentions for the upcoming week. This practice enhances focus and prevents overwhelm.

Adapt and Iterate

Allen’s method is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Continuously adapt and iterate on the system to suit your unique preferences, workflow, and circumstances.

My Book Highlights & Quotes

Your mind is for having ideas, not holding them.

If you don’t pay appropriate attention to what has your attention, it will take more of your attention than it deserves.

You can do anything, but not everything.

You don’t actually do a project; you can only do action steps related to it. When enough of the right action steps have been taken, some situation will have been created that matches your initial picture of the outcome closely enough that you can call it “done.”

Much of the stress that people feel doesn’t come from having too much to do. It comes from not finishing what they’ve started.

Through its straightforward approach and actionable techniques, the book empowers readers to take control of their tasks, prioritize effectively, and achieve their goals with greater ease.

By embracing Allen’s methods, you can cultivate a sense of clarity and focus amidst the chaos of daily life, ultimately leading to increased efficiency and reduced stress.

So, why wait? Dive into Allen’s insightful guidance and start experiencing the transformative power of getting things done effortlessly.

I am incredibly grateful that you have taken the time to read this post.

Do you want to get new content in your Email?

Do you want to explore more?

Check my main categories of content below:

- Agile

- Blog

- Book Notes

- Career

- Leadership

- Management

- Managing Yourself

- Productivity

- Project Management

- Technology

- Weekly Pulse

Navigate between the many topics covered in this website:

Agile Art Artificial Intelligence Blockchain Books Business Business Tales Career Coaching Communication Creativity Culture Cybersecurity Design DevOps Economy Emotional Intelligence Feedback Flow Focus Gaming Goals GPT Habits Health History Innovation Kanban Leadership Lean Life Managament Management Mentorship Metaverse Metrics Mindset Minimalism Motivation Negotiation Networking Neuroscience NFT Ownership Parenting Planning PMBOK PMI Politics Productivity Products Project Management Projects Pulse Readings Routines Scrum Self-Improvement Self-Management Sleep Startups Strategy Team Building Technology Time Management Volunteering Work

Do you want to check previous Book Notes? Check these from the last couple of weeks:

- Book Notes #123: The Personal MBA by Josh Kaufman

- Book Notes #122: The First 20 Hours by Josh Kaufman

- Book Notes #121: A World Without Email by Cal Newport

- Book Notes #120: Storynomics by Robert McKee and Thomas Gerace

- Book Notes #119: Getting Things Done by David Allen

Support my work by sharing my content with your network using the sharing buttons below.

Want to show your support tangibly? A virtual coffee is a small but nice way to show your appreciation and give me the extra energy to keep crafting valuable content! Pay me a coffee: